I learned the hard way that pain, and my reaction to it, is one of the useful signals a therapist uses to evaluate the progress of your rehabilitation.

… in the shoulder. What I mean to say is that sometimes physical therapy can be a little painful.

Before I get into too much trouble, let me explain.

My trail back runs through the gym.

The scapula (also called the “shoulder blade”) is paper-thin and can break. But shattering it is fairly rare.

I knew that at some point, I would have to start exercising my shoulder if I wanted to recover fully. The way it was explained to me, I’d need to give my body time to heal first. Then, I would have to strengthen my shoulder and get as much motion and flexibility back into the joint as possible. Once that was accomplished, my orthopedic surgeon would take a closer look at the remaining damage resulting from my accident.

Getting better can be tough work.

My fall last October shattered my scapula. And even though that paper-thin bone would eventually grow back together, I needed to keep working on the joint to ensure I regained most of my arm’s motion.

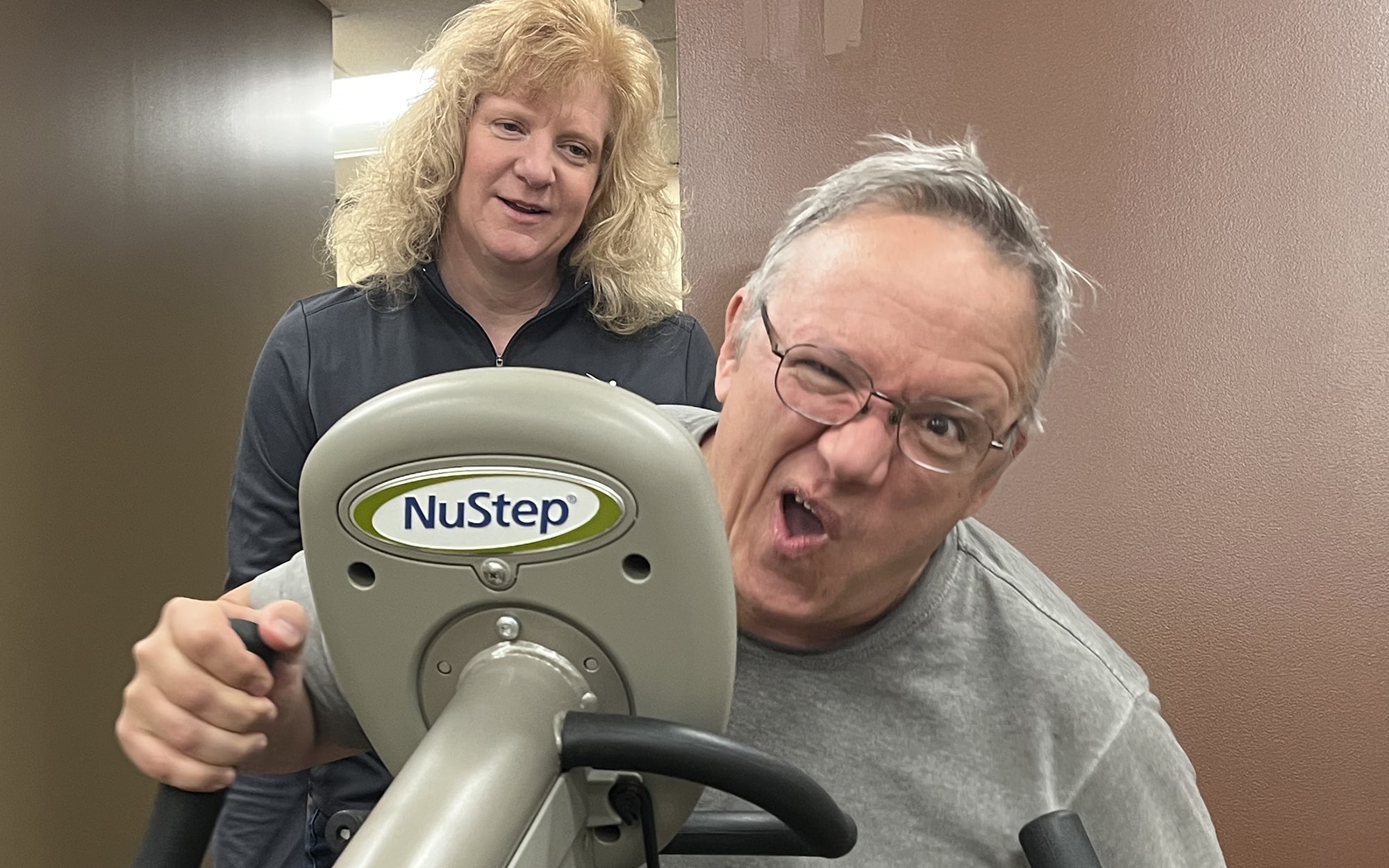

Of course, that has meant lots of exercising and stretching. Three days a week, I’m at ORA’s clinic in Northwest Davenport, doing my best to push weight around, stretch elastic bands, bounce balls off walls, and a host of other exercises meant to test, tweak, and build up the muscles in my right shoulder as they attempt to resume the job they were performing before they were so rudely interrupted.

As rehabilitation gyms go, the facilities on Northwest Boulevard seem to be well-supplied and maintained, with a variety of machines and equipment. To the untrained eye, like mine, it looks like your regular hotel gym with just one or two pieces of the same equipment and plenty of television monitors. But on closer inspection, you find every piece of equipment – from brightly-colored stretchy band to steel-grey treadmill – has a specific purpose.

Getting back to life takes perseverance (and a little perspiration).

Therapists use these tools of their trade to help patients regain strength and flexibility. The focus is not on building beach bodies but rather on making it possible for people to move again and get back to the things that matter most in their lives.

Achieving that means you have to rediscover muscles that may have lost their tone while immobilized in a cast or sling. Sometimes it means re-learning basic motions and physical tasks – like putting on a winter jacket – that accommodates your limited mobility or weakened condition.

I often see folks working on re-gaining their balance, teaching their body how to stabilize itself again. It can be hard work and failure is a common occurrence. Most folks might get discouraged and give up, resigning themselves to a “new normal” of limited mobility, pain, and frustration.

But these patients are not doing this alone.

Physical therapists are there by their side, doing what they do best: coaching, collecting, and encouraging.

And in my case, gratefully inflicting a little bit of pain.

Yes, there is such a thing as “good” pain.

Yes, a little bit of pain can be a good thing.

If you think about it, pain serves a purpose. It’s how your body tells your brain that something is wrong and that it needs to find some relief. Pain, and your body‘s reaction to it, are some of the useful signals a therapist uses to evaluate the progress of your rehabilitation.

When I asked my therapist, ORA Orthopedics’ PT, Kathryn Ellsworth, about my pain signals, and how she used them in my therapy, she explained it this way:

“I monitor both non-verbal and verbal reports of pain and adjust my therapy accordingly. I know that what we do is going to produce some discomfort because we’re trying to address the damage to the joint and surrounding soft tissue. But I’m careful because causing too much pain can be counter-productive and could be hard to relieve.”

So … it could be worse. I guess I should stop complaining about being so sore all the time.

“Some people confuse the two. There is actually a big difference between soreness resulting from muscle fatigue after a rehab session and pain caused by some kind of trauma a person has suffered – like falling ten feet onto a cement stone.”

Okay, I kind of deserved that.

My therapist can read me like a book … and it’s probably Dr. Seuss.

So, apparently, my reactions to the aches and pains I suffer through during my therapy (usually consisting of grimaces and bad Dad-jokes) are just part of what Kathryn takes into consideration as she’s guiding my recovery. She observes how these verbal and nonverbal cues compare to what she’s feeling inside my shoulder as she works it through a series of motions.

As the shoulder begins to resist the pressure to move, Kathryn looks to see if I’m expressing some level of pain. And I usually am. An eye roll might mean one thing. A wince or a muffled scream might mean something else.

Actually, I rarely scream during physical therapy because 6:15 am is far too early in the morning for that kind of behavior – and I’ve only had one cup of coffee, so I’m only half awake.

In reality, the pain isn’t usually too severe. Kathryn will push or pull on my arm and my shoulder will sometimes tweak or twinge. It can be a sudden snapping sensation, like someone shooting my shoulder with a rubber band. If not that, I’ll experience a dull, throbbing sensation – like when my arm feels it isn’t fully back in the shoulder socket – which it isn’t.

Kathryn compares her knowledge of physiology with my description of how things feel and creates a new data point to track my recovery.

My trail back will be a long one. And I knew that at times it would be painful as well. But it’s good to know all the pain serves a purpose.

The trail doesn’t end in pain … at least it doesn’t have to.

It’s also good to know that there are ways to deal with the pain that goes beyond taking a dose of “Vitamin I“ (that’s how ORA PA, John Tyron, referred to ibuprofen during my last visit).

But that’s a story for another day. I hope you’ll stay with me on this trail as we go down it together.